Rhizophagus clarus

Preparing Clean Healthy Spores for Shipment

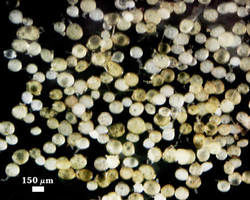

Extracted Population of Spores

Of all medium-sized glomoid species, R. clarus is one of the most susceptible to degradation by parasitism. All of the isolates of this species in the collection cannot be stored longer than 9-12 months before most, if not all, of the spores will no longer be viable. Bacteria and some fungi appear to readily colonize the thick mucilagenous layer of the spore wall and from there invades the lumen of many spores. The range of phenotypes resulting from this activity are pictured below after they were separated from the general population (seen at left). Many glomoid species have a mucilagenous layer (albeit generally much thinner) which may increase their susceptibility to parasitism or abundant surface colonization. Therefore, spores of most glomoid species require a cleaning step that removes surface contaminants, even from healthy-appearing spores.

Parasitized or Dead Spores

Spores with black, orange, red, or brown contents usually are heavily parasitized, generally from colonization of the lumen by saprophytic fungi or actinomycetes. Hyphae will grow extensively from many of these spores after < 24 hr. incubation, even at 4°C (shown in the photo above). These spores must be excluded immediately after extraction to avoid contamination of healthy spores.

Spores with Irregular Contents

Lipid droplets tend to be evenly distributed in healthy spores (see below). Those with varying degrees of patchiness in density or color (usually discoloration) indicate degradation or other negative impact. Some of these spores do not contain parasites, but since they are not separable from those that do contain them, all are removed. Parasitized spores appearing healthy first take on this appearance.

Opaque Spores

When the spore wall has become partially degraded from presumed bacterial activity, spores take on the appearance of being coated with a filmy opaque layer. This is in contrast to shiny surfaces and clear contents of healthy spores (see below). These opaque spores still are infective and so contents have not be parasitized. Given signs of microbial activity, these spores also are removed.

Healthy spores that have shown little change over at least 24 hr are considered ready for shipment in sterile sand. Rhizophagus clarus shows inherent variation in color (white to dark yellow), and so it is important not to use these color differences as a criterion in culling “deviants” from the spore population. Another common variation in appearance of contents is a merging of lipid droplets so that the center of the spore lumen appears transparent. The important consideration, apart from this variation, is that spore contents are clear, relatively homogeneous, and the spore surfaces are “clean” and smooth after prolonged incubation.